As IF IT WEREN’T enough

that Christopher Columbus had dedicated the New

World to her,

and that Andrew White had dedicated Maryland to her, and that Bishop

Carroll had dedicated his See of Baltimore to her, the 1846

convention of American

Roman Catholic bishops declared the Virgin Mary

to be “Patroness

of the United States.”

The

first two years under her patronage enriched the

national government considerably. The Oregon

territory and the Southwest joined the Union. As did

California, with its bursting veins of gold. The blessings

had their downside, however. They precipitated a

corresponding increase in intersectional tensions that

erupted in a devastating

interstate bloodbath some historians call the Civil War.

In that war, the Patroness of the

United States dealt as cruelly with the enemies of her

protectorate as the vengeful goddess Ishtar did with the

enemies of ancient Babylon.

In

February 1849, “Pio Nono” (the popular name for Pope Pius

IX; there’s a boulevard

named after him in Macon, Georgia) issued an encyclical that

colored America’s Patroness

with the fearsome aspects of Ishtar. The encyclical, entitled Ubi primum (“By whom

at first”), celebrated

Mary’s divinity, saying:

| The resplendent glory of her merits, far exceeding all the choirs of angel, elevates her to the very steps of the throne of God. Her foot has crushed the head of Satan. Set up between Christ and his Church, Mary, ever lovable, and full of grace, always has delivered the Christian people from their greatest calamities and from the snares and assaults of all their enemies, ever rescuing them from ruin. |

Holy as

she may sound, a

Satan-bashing, life-saving Virgin Mary is a fabrication

of sacred sun worship tradition. The Bible does

prophesy that Satan’s serpentine head will be violated.

But not by Mary.

At Genesis 3:15, we read God’s vow that Satan’s seed will

be bruised by the seed of Eve. It may be argued that Eve’s

seed was Mary.

But according to the inspired understanding of the

apostles, it was Jesus.

At Romans 16:20 Paul promises a Roman congregation that

“the God of peace shall bruise Satan under your feet.” Nor

was Mary given power to deliver people from their enemies.

Only the “one mediator between God and men, the man Christ

Jesus” (1 Timothy 2:5), “a name which is above every

other name” (Philippians 2:9), is a divinely-authorized deliverer.

No, the

Mary of Ubi Primum

will not be found anywhere in the Bible. But then Pio

Nono, the first pope

ever to be declared Infallible, carried about a

rather famous theological ignorance. His private

secretary, Monsignor Talbot, defended Pio’s ineptitude in

a letter cited by Jesuit author Peter de Rosa in his Vicars of Christ:

| As the Pope is no great theologian, I feel convinced that when he writes his encyclicals he is inspired by God. Ignorance is no bar to infallibility, since God can point out the tight road even by the mouth of a talking ass. |

The truth of the matter, according to J.C.H. Aveling, is

that throughout Pius IX’s long reign (1846-1878), most of his theology was written by Jesuits.

On December 8, 1854, Superior General Beckx brought three

hundred years of Marian devotion to a glorious climax with

Ineffabilis Deus (“God indescribable”), the encyclical

defining the Immaculate

Conception, the extrascriptural doctrine that

Mary, like Jesus, was conceived and remained free of sin:

| The doctrine which holds that the most blessed Virgin Mary, in the first instant of her conception, by a singular grace and privilege granted by Almighty God, in view of the merits of Jesus Christ, the Saviour of the human race, was preserved free from all stain of original sin, is a doctrine revealed by God and therefore to be believed firmly and constantly by all the faithful. |

Ineffabilis Deus mobilized the United States Congress to

pass extraordinary legislation. Congress became suddenly

obsessed with expanding

the Capitol’s dome. According to the official

publication The Dome of the United States Capitol: An

Architectural History (1992), “Never before (or since) has an addition to the

Capitol been so eagerly embraced by Congress.”

Within days of Pio Nono’s definition of the doctrine of Immaculate Conception,

legislation was rushed through Congress that effectively

incorporated the new

Vatican doctrine into the Capitol dome’s crowning

architectural platform, its cupola.

A week

following Ineffabilis Deus Philadelphia architect Thomas

Ustick Walter, a Freemason,

completed his drawings for the proposed dome. It would be

surmounted by a bronze

Marian image which would come to be recognized as

“the only authorized Symbol of American Heritage.”

Her classical name was Persephone,

Graeco-Roman goddess of

the psyche, or soul, and leading deity in the

Eleusinian Mysteries of ancient Greece. Persephone was

abducted by Saturn’s son, Hades, and made queen-consort of

his dominion, the underworld. Persephone was distinguished for her Immaculate Conception

– described by Proclus, head of the Platonic

Academy in Athens during the fifth century of the

Christian era, as “her undefiled transcendency in her

generations.” In

fact, most of the statues of Persephone in the

Christianized Roman Empire had been simply re-identified

and re-consecrated as the Virgin Mary by missionary adaptation.

| My Comments NOT the

author Tupper Saussy. |

|

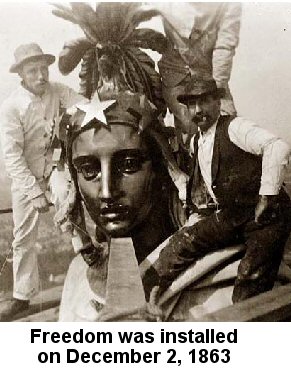

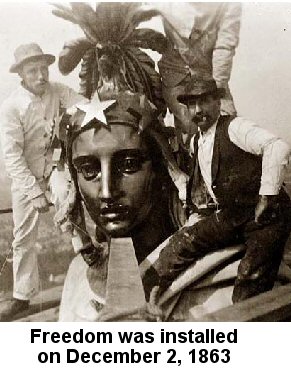

Please stop and

understand the Timeline between 1855 to 1863

1855 Thomas

Crawford begins sculpting the statue of Freedom in his

studio in Rome,

Italy.

December 2, 1863 Final section installed a top the Capitol. This was done during the civil war. We are lead to believe the Vatican was on the side of the South. In reality they(Jesuits) were controlling both sides. Why? Because in the middle of the civil war they erect a Roman goddess(Mary) masquerading has "Freedom." They already new who was going to win the Civil War. I make this statement not to down play Lincoln, he was just in the middle of a big mess. He knew who was behind the war and did not go along with the Vatican's Script. The same with John F. Kennedy. Both men knew who was behind world rule and both men paid the price. |

| Another word for Freedom is Mary. |

Congress appropriated $3,000

for a statue of Persephone. President Franklin

Pierce’s Secretary of

War, Jefferson Davis,(Davis suggested the

helmet instead of a Liberty cap, he would soon become

president of the Confederacy) awarded the

commission to a famous young American sculptor named

Thomas Crawford. Crawford lived and worked in Rome. His

reputation had been established with a statue of Orpheus

which, when exhibited in Boston in 1843, was the first

sculptured male nude to be seen in the United States.

Since another of Persephone’s ancient names was Libera

(“Liberty”), Crawford named

his Persephone “Freedom.” His work has worn this title

ever since.

After two years of

labor in the shadow of the Gesu, Crawford completed a

plaster model of Freedom.

Her right hand rested on a sword pointing downward. Her

left hand, against which leaned the shield of the United

States, held a laurel wreath. She was crowned with an

eagle’s head and feathers mounted on a tiara of pentagrams, some

inverted, some not. When ultimately cast in

bronze, Freedom

would reach the height of nineteen feet, six inches – a sum perhaps

deliberately calculated to pay homage to the work’s final

destination, the Beast of Revelation at Lot 666, for nineteen

feet, six inches works out to 6+6+6 feet, 6+6+6 inches.(do the math)

Freedom would stand

upon a twelve-foot iron pedestal also designed by Thomas Crawford. The

upper part of the pedestal was a globe ringed with the

motto of the Bacchic Gospel, E PLURIBUS UNUM, while the

lower part was flanked with twelve wreathes (the twelve

Caesars?) and as many

fascia, those bundles of rods wrapped around

axe-blades symbolizing Roman

totalitarianism.

Crawford wanted his

sculpture to be cast at the Royal Bavarian Foundry in

Munich (where Randolph Rogers’ great ten-ton bronze doors

leading to the Capitol rotunda were cast), while architect

Thomas U. Walter preferred Clark Mills’ foundry, near

Washington. Their transatlantic argument ended abruptly

when Crawford

died in London on September 10, 1857, of a tumor behind

his left eye.

In that same year, 1857,

the United States Supreme Court handed down Dred Scott vs.

Sanford, a decision which most historians agree ignited the Great American

Civil War. The opinion was written by the Roger

Brooke Taney, who succeeded John Marshall as Chief

Justice. A devout

Roman Catholic “under the influence of the Jesuits most of his long life”

according Dr. Walsh’s American Jesuits, Taney held that

Negro slaves and their descendants could never be State

citizens and thus could never have standing in court to

sue or be sued. Nor could they ever hope to be United

States citizens since the Constitution did not create such

a thing as “United States

citizenship.”

Taney’s

opinion was widely suspected of being part of a plot to

prepare the way for a second Supreme Court decision that

would prohibit any state from abolishing slavery. American slavery would

become a permanent institution. This is exactly

what happened, although not quite as everyone supposed it

would. First, slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment (1865).

Then, the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) created a new national

citizenship. Unlike State citizenship,

which was denied to Negroes, national citizenship was

available to anyone as long as they subjected themselves

to the jurisdiction of the United States-that is, to the

federal government, whose seat is the District of Columbia, “Rome.”

What is so remarkably Jesuitic about the

scheme that proceeded out of Roger Taney’s opinion is

that slavery was sustained by the very amendment that

supposedly abolished it. Amendment Thirteen

provides for the abolition of “involuntary servitude,

except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall

have been duly convicted.” In our time the federally

regulated communications media, with their continually

exciting celebration of violence and drug-use, have subtly

but vigorously induced youthful audiences to play on a

minefield of complementary criminal statutes. The fruit of this

collaboration is a burgeoning national prison population

of men and women enslaved constitutionally.

American slavery has become a permanent

institution.

Reaction to Taney’s decision animated Abraham Lincoln to

immerse himself in abolitionist rhetoric and challenge

Stephen A. Douglas for the Senate in 1858.... MEANWHILE in

Rome, Freedom’s plaster

matrix was packed into five huge crates and

crammed, with bales of rags and cases of lemons, into the

hold of a tired old ship bound

for New York, the Emily Taylor. Early on,

the Emily sprang a leak

and had to put in to Gibraltar for repairs. Once the

voyage was resumed, stormy weather caused new leaks.

Despite attempts to lighten her load by jettisoning the

rags and the citron, things got so bad she put in to

Bermuda on July 27, 1858. The crates were placed in

storage, and the Emily

was condemned and sold.

In

November, Lincoln lost his bid for Douglas’ seat in the

Senate, and in December, another ship, the G.W. Norton,

arrived in New York harbor from Bermuda with some of the

statuary crates. By March 30, 1859 all five crates

had been delivered to the foundry of Clark Mills on

Bladensburg Road, on the outskirts

of the District of Columbia, where the process of

casting the Immaculate

Virgin into bronze and iron was begun.

Lincoln

opposed Stephen Douglas again in 1860, this time for the

Presidency, and this time victoriously. The northern

states rejoiced. The southern states, fearing

Lincoln would abolish slavery, prepared to secede. “The tea has been thrown

overboard!” shouted the Mercury, of Charleston,

South Carolina, capital of American Scottish Rite Freemasonry.

“The revolution of 1860

has been initiated!”

By

Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, six states had

seceded from the Union. In April, General Pierre Beauregard, a

Roman Catholic who resigned his Superintendency

of West Point to join the Confederacy, fired on the

United States military enclave at Fort Sumter and

brotherly blood began flowing. Jefferson Davis,

who five years earlier had commissioned Crawford to sculpt the

Immaculate Virgin,

served as President of the rebellious Confederate States of

America. In historian Eli N. Evans’ book on Judah P.

Benjamin, I happened upon a strange and interesting link

between Davis and the

Vatican.

While a young Protestant

student at the Roman Catholic monastery of St.

Thomas College in Bardstown, Davis had pled to be received

into the Catholic faith, but was “not permitted to con-vert.”

He remained “a hazy

Protestant” until his confirmation into the

Episcopal Church at the age of fifty. Despite outward

appearances of rejection, the Confederate President maintained a vibrant

communion with Rome. No one was more aware of

this than Abraham Lincoln. At an interview in the White

House during August 1861, Lincoln confided the following

to a former law client of his, a Roman Catholic priest

named Charles Chiniquy, who published the President’s

words in his own autobiography, Fifty Years In The Church

of Rome:

|

“I feel more and more every day,” [stated the

President] “that it is not against the Americans

of the South, alone, I am fighting. It is more against

the Pope of Rome, his Jesuits and their slaves.

Very few

Southern leaders are not under the influence of the

Jesuits, through their wives, family

relations, and their friends.

“Several members of the family of Jeff Davis

belong to the Church of Rome. Even the Protestant

ministers are under the influence of the Jesuits

without suspecting it. To keep her ascendency in

the North, as she does in the South, Rome is doing here

what she has done in Mexico, and in all

the South American Republics; she is paralyzing,

by civil war, the arms of the soldiers of liberty.

She divides our

nation in order to weaken, subdue and rule

it....

“Neither Jeff Davis not any one of the Confederacy

would have dared to attack the North had they not

relied on the

promises of the Jesuits that, under the

mask of democracy, the money and the aims of the Roman

Catholics, even the arms of France, were

at their disposal if they would attack us. I pity

the priests, the bishops, and monks of Rome in the

United States when the people realize that they

are in great

part responsible for the tears and the blood

shed in this war. I conceal what I know,

for if the people knew the whole truth, this war

would turn into a religious war,and at once, take

a tenfold more savage and bloody character....

|

The

Great Civil War rampaged for another year. In autumn of

1862, the Confederacy’s invasion of the Union was

defeated at the Battle of Antietam in Sharpsburg,

Maryland. As

if in celebration, the Immaculate Virgin was moved from the

foundry and brought to the

grounds of the Capitol construction site. The

lower floors of the building were teeming with the traffic

of a Union barracks and makeshift hospital. Above all this

loomed Thomas U. Walter’s majestic cast-iron dome, patterned after

that of St. Isaac’s

Cathedral in St. Petersburg, Russia.

In

March 1863, Freedom

was mounted on a temporary pedestal, “in order that the

public may have an opportunity to examine it before it is

raised to its destined position,” as stated in Walter’s

Annual Report dated November 1, 1862. One would expect

photographers to be climbing all over themselves to make

portraits of “the only

authorized Symbol of American Heritage” while she

was available for

ground-level examination. America’s pioneer

photographer, Matthew Brady, had shot a comprehensive

record of the Capitol under construction, including

portraits of both Capitol architect Thomas U. Walter and

Commissioner of Public Buildings Benjamin B. French. But

neither Brady nor anyone else photographed Freedom while she

was available for closeups. Why? Was

there a fear that perhaps some Protestant theologian

might raise a hue and cry about the sun worship icon

about to dominate the

Capitol building?

Apparently, not too many Protestants

ever examined Freedom at

ground-level. The District of

Columbia was still virtually a Roman Catholic enclave.

Moreover, the nation in

1863 had been drastically reduced in size. The secession

of the southern states had left only twenty-two northern

states, and these twenty-two were heavily populated by

Catholic immigrants from Europe and Ireland.

“So incredibly large,” we recall from Sydney E. Ahlstrom’s

Religious History of the American People, “was the flow of immigrants

that by 1850 Roman Catholics, once a tiny and ignored

minority, had become the country’s largest religious

communion.” Thus, Crawford’s towering

goddess was being examined mostly by Roman Catholic eyes,

eyes that could not help but see in her the dreadnaught

Mary described by Pius IX in Ubi Primum: “ever lovable, and full

of grace, set up between Christ and his Church, always

delivering the Christian people from their greatest

calami-ties and assaults of all their enemies, ever

rescuing them from ruin.”

The

war rapidly advanced to conclusion while Freedom held forth on

the east grounds of the Capitol. The Union forces under

Burnside lost to Lee at Fredericksburg, but Rosecrans

defeated the Confederates at Murfreesboro, and Grant took

Vicksburg. In summer, Lee’s second attempt to invade

the North failed at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. By

fall, Grant won the Battles of  Chattanooga and

Missionary Ridge with Sherman and Thomas. By the end of November 1863,

the Union had taken Knoxville, and the Confederacy found

its resources exhausted and its cause hopelessly lost.

Chattanooga and

Missionary Ridge with Sherman and Thomas. By the end of November 1863,

the Union had taken Knoxville, and the Confederacy found

its resources exhausted and its cause hopelessly lost.

Chattanooga and

Missionary Ridge with Sherman and Thomas. By the end of November 1863,

the Union had taken Knoxville, and the Confederacy found

its resources exhausted and its cause hopelessly lost.

Chattanooga and

Missionary Ridge with Sherman and Thomas. By the end of November 1863,

the Union had taken Knoxville, and the Confederacy found

its resources exhausted and its cause hopelessly lost.

On November 24, a steam-operated

hoisting apparatus lifted the Immaculate Virgin Mother of God’s first section

to the top of the Capitol dome and secured it. The second

section followed the next day. Three days later, in a

driving thunderstorm, the third section was secured. The

fourth section was installed on November 31.

At quarter past noon December

2, 1863, before an enormous crowd, the Immaculate Virgin’s

fifth and final section was put into place. The

ritual procedure for her installation is preserved in

Special Order No. 248 of the War Department. Her

head and shoulders rose from the ground. The

three-hundred-foot trip took twenty minutes. At the moment

the fifth section was affixed, a flag unfurled above it. The

unfurling was accompanied by a national salute of

forty-seven gunshots fired into the Washington

atmosphere. Thirty-five shots issued from a field

battery on Capitol Hill. Twelve were discharged from the

forts surrounding the city. Reporting the event in the December 10 issue of

the New York Tribune, an anonymous journalist echoed the

qualities that Pius IX had given Mary:

| During more than two years of our struggle, while the national cause seemed weak, she has patiently waited and watched below: now that victory crowns our advances and the conspirators are being hedged in, and vanquished everywhere, and the bonds are being freed, she comes forward, the cynosure of thousands of eyes, her face turned rebukingly toward Virginia(remember she is facing East) and her hand outstretched as if in guaranty of National Unity and Personal Freedom. |

If

Tribune readers felt more nationally united and personally

free because Freedom was

glaring at rebellious

Virginia and outstretching her hand to her

beloved America, they

were deceived. For the goddess faced in precisely

the opposite direction! She

faced east, as she does to this day, faced east across Maryland, the “land of Mary,” across

the Atlantic, toward her

beloved Rome. In fact, neither hand outstretches

in any direction. Both are at rest, one on her sword, the

other holding the laurel wreath. And her forty-seven

Jupiterean thunderbolt-gunshots? They were

a tribute to the Jesuit bishop who had placed the District of

Columbia under her protection. For December 2,

1863 tolled the forty-seventh

year from Jesuit John Carroll’s last full day

alive, December 2, 1815!

| My Comments |

| What did the author

mean when he said "Freedom

was glaring at rebellious

Virginia."? Virginia was named after

Queen Elizabeth I of England who reign for 45 years

as a Protestant Queen. She was the Queen when

Rome launched the Spanish Armanda in 1588. Freedom is also facing East!! Freedom is symbolizing the Immaculate Conception which is Rome's Queen of Heaven Mary. which is sun worship. Eze 8:16 And he brought me into the inner court of the LORD'S house, and, behold, at the door of the temple of the LORD, between the porch and the altar, were about five and twenty men, with their backs toward the temple of the LORD, and their faces toward the east; and they worshipped the sun toward the east. |

ONCE the pressures of

the installation were over, an exhausted but relieved

Capitol Architect Thomas U. Walter wrote his wife, Amanda,

at their Philadelphia home, to say that “her ladyship looks placid and

beautiful – much better than I expected, and I

have had thousands of congratulations on this great event,

and a general regret was expressed that you were prevented

from witnessing this triumph.” Someone else had missed the triumph, too,

someone who by all the rules of protocol should have been

there no matter what: the Commander-in-Chief of the United

States Armed Forces, whose

War Department had engineered the whole Capitol

project from top to bottom–President Abraham

Lincoln. At noon on the day the

temple of federal legislation was placed under the

patronage of Persephone, Freedom, Wife of Hades, Queen

of the Dead, Immaculate

Virgin of Rome, Protectress of the Jesuits, Protectress

of Maryland, and

Patroness of the United

States, the record shows that Lincoln sequestered

himself inside the White House, touched with “a fever.” A telling detail.

But the

sacred iconography

was still not complete. The engineers began now preparing

the interior of the dome, its canopy, for a massive

painting Congress had approved back in the spring of 1863.

This painting would depict George Washington undergoing

the secular version of the canonization of Ignatius Loyola. It

contains even more data useful to our understanding of the

character and provenance of American government. We

examine this masterpiece in our next chapter. Click here